Patient Access And Control: The Future Of Chronic Disease Management?

The Investments In A Wearables Future

Dec 17, 2014Say Goodbye to the Original Yahoo Directory

Dec 17, 2014Sufferers of chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the United States are among the more active practitioners of disease self-management. It involves, among other disciplines, rigorous self-monitoring of blood glucose and blood pressure levels, strict dietary discipline and, possibly, self-administering of insulin injections. It is a complex program of continuous diagnosis and treatment that also entails the regular communication of patient data to, and sharing among, multiple care providers.

Healthcare providers are of course using this data to help monitor and prescribe treatment. But they’re also beginning to integrate the data into patient electronic medical records (EMRs). In 2013, Boston-based Partners HealthCare, for example, became among the first U.S. providers to integrate CKD-related data from at-home devices with the electronic records held in its doctors’ offices. Home patients can access their data and track their progress on a web-based portal.

CKD sufferers tend to be extremely knowledgeable about their own conditions, because the disease’s management features prominently in their everyday activities. They thus have much to gain from better access to their EMRs (For a study of the potential benefits of EMRs to CKD treatment, see “Electronic health records: A new tool to combat chronic kidney disease?” (multiple authors), NIH National Library of Medicine). They’re not the only ones. The U.S. Center for Disease Control estimates that about half of all adult Americans suffer from one or more chronic health conditions. In addition to CKD, these may include cancer, heart disease, diabetes, back pain, arthritis and others.

Balancing Access and Privacy

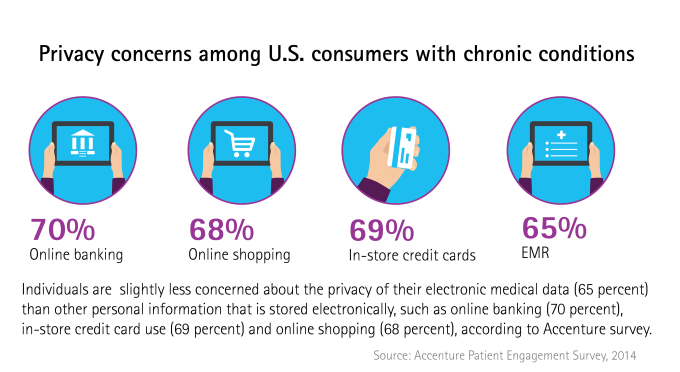

Whether they self-manage or not, chronic disease patients clearly want access to their medical records, even if it means compromises over privacy. In a recent Accenture survey of 2,011 U.S. consumers with chronic conditions, 69 percent of those polled believe they should have the right to access their medical records. Over half (51 percent) say that being able to access their data online outweighs the privacy risks involved. In an even more emphatic statement, nearly 9 in 10 of those polled (87 percent) state the desire to gain control over their records.

However, most of the survey group (55 percent) currently has little, if any, such control. The ability to exercise control also differs depending on the type of chronic illness individuals have: Those with heart disease, for example, are much more likely to enjoy some control than those suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Control starts with access. Americans may be digitally literate and active users of online health information, but chronic disease patients in the survey say the main barrier to obtaining records is their lack of knowledge about how to do so. In this context there is concern that some groups of patients – notably the elderly – will become less able to access their online records over time.

Help is on the way for those who have at least some knowledge of how to use a mobile device or computer to access the Internet, as developers are creating apps to view and interact with their medical records. The government-supported “Blue Button” should also help, enabling one-click access to an individual’s medical data from health-provider websites.

The Meaning of Control

What will patients do with the control they gain? For one thing, they are likely to determine privacy settings themselves. A study published in 2012 by academics from Clemson University and Indiana University indicated that patients seek to control which types of care providers (primary care physicians, other specialists treating them and non-treating specialists) can view their records and which types of information (sensitive versus less sensitive) should be open to different categories of provider.

Ultimately, however, patients will want their control to lead to better diagnoses and better treatment. One of the defining attributes of health data systems has been their proprietary nature, leading to siloes of information that are not always shared efficiently, even when involving a single patient with a single chronic condition. The patient is usually the only person that has been present at every consultation over the course of treatment, and may be best placed among the different actors to ensure the right data is made available to all the right specialists.

Chronic disease sufferers – who are likely to have consulted multiple specialists over several years, and about whom large volumes of data have likely been generated – are particularly well placed to take advantage of such control. For these individuals, access may be more than power; it may be relief.

Source: Techcrunch.com